Native American Bear Story…

“Muinej The Bear’s Cub” – A Mi’kmaq Bear Story & Folktale Retold – A Native American Legend

THE BOY WHO WAS RAISED BY BEARS! A NATIVE CANADIAN MI’KMAQ BEAR STORY RETOLD & FREE TO READ…

Introduction by Brian Alan Burhoe.

Bears have long appeared in folktales and animal stories worldwide.

Especially among Northern Peoples.

Those of us of Northern ancestry, whether Northern European (Nordic, Slavic, Germanic, Celtic and Anglo-Saxon) or First Nations of North America, come from cultures that believed that Bearkind was Humankind’s closest blood relative. Hence, for instance, the numerous stories of bear-human children among the Vikings, Germans and Druidic Celts. Many First Nations have family groups who call themselves the Bear Clan, explaining they have actual bear blood in their veins or met bears in sacred visions.

Talking bears, bear-human hybrids and human children adopted and raised by loving mama bears are common story themes in both Old and New World oral traditions. Even J. R. R. Tolkien wrote about Beowulf and “Bear’s Son Tales in European folklore.”

Here’s my retelling of a favourite bear story, a local First Nations folktale I read first as a boy…

“Muinej The Bear’s Cub” A Bear Story

In a younger Turtle Island, before the coming of foreign seafarers and clamoring machines and civilized greed, when the forests were greener and the trees were bigger, there lived a Mi’kmaq boy named Mikinawk.

Mikinawk never knew his real father who had been killed during a battle with another tribe. Instead, he was raised by a brutal braggart of a man who believed his new wife loved her son more than him. The mother often had to stop her new husband from beating the boy.

But eventually the man seemed to accept the boy and began to speak kindly to him and she secretly shed tears of thankfulness.

The day came when Mikinawk’s stepfather said, “Woman, this is the day Mikinawk will start on the path to manhood. I will take him hunting with me.”

“But Mikinawk is not yet of age,” she said.

“He will be safe with me. Have I not accepted him as my own? Today, we will only hunt rabbits.”

So she agreed to let them set out in the forest.

On his previous hunt, when he had gone into the rocky Spirit Hills where other men of the band rarely went, the stepfather had spotted a cave. And an idea had come to him then.

They traveled for what the boy thought was a long time. Even he could identify rabbit droppings and pathways in the grass. But his stepfather kept them moving on.

And then the man whispered, “Listen! I hear voices of other men!”

The boy listened. All he could make out were bird calls and the splashing of a nearby river.

“I don’t hear voices,” whispered Mikinawk.

“I do. They are warriors of the band we once fought, I’m sure. The ones who killed your father. Quick! See that cave? Hide in there! I will lay under one of those cedar trees and guard us. Stay in the cave until I call you. Go!”

And so Mikinawk ran into the cave, crawling deep into its darkness.

Laughing, the man followed his stepson, keeping out of sight in the trees. He picked up a birch pole he had cut and hidden on his last trip here. The hill was covered with big boulders left there long ago, say the old story tellers, by Ice Spirits. He scampered up the hill and stuck the pole behind a boulder and set it rolling down the hill. It crashed into place in the cave’s opening, blocking the boy’s way out. Trapping the boy he hated. He shouted out just one word, “Starve!”

But the shaking of the earth had loosened a bigger boulder further up the hill. Or perhaps it was the Ice Spirits. Hearing something behind him, the stepfather had only time to turn and see the rolling rock when it hit him.

Almost feeling the weight of the stone walls of the cave, Mikinawk bravely fought his loneliness and fear. He listened intently for any sound beyond the great darkness that had swallowed him when the boulder had crashed into place. But he was only five and he wanted his mother, so he eventually let out a big sob.

He was startled by a voice from deeper in the cave.

“Who is there? Who are you?” The voice was not human, but seemed to be of something small and young like him.

“I am Mikinawk. Who are you?”

“I am Nidap. This is my sister Ebit.”

“What animals are you?” he said into the darkness.

“We are bear cubs. What are you?”

“I am a human.”

“Oh!” came two voices filled with fear.

“I am a friend,” said Mikinawk, hiding his own fear. “This is a time for friendship.”

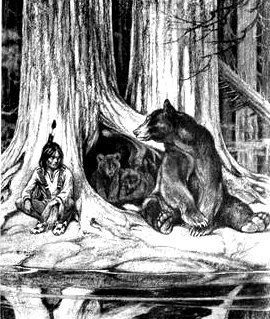

And then there was a crunching noise and sunlight spilled into the cave as the boulder was rolled away.

“Ebit! Nidap!” came a deep growling voice. “What is happening? There is the smell of humans here.”

And Giju’muin, a big mother bear, crawled into the cave. Snuffing noisily, her hot breath poured onto Mikinawk’s face.

“You are dangerous, little human. I –”

“He said he is a friend,” came another voice, who must have been the sister bear.

Giju’muin thought about this. She had found the body of a man on the hill. Knowing that the humans would blame her for the death if discovered, and kill her and her cubs, she had carried the body and thrown it in the fast flowing river.

“Why are you here, little one?” she asked the boy.

“My stepfather must have done it. He hates me. But my mother loves him. And the men of our band praise him as a mighty warrior. I don’t know if I can go home.”

Now that there was light in the cave, the two cubs moved toward him and sniffed him. The she-cub asked, “Can he stay with us, Mother?”

The mother bear thought again. She couldn’t let him return to his people and tell them about her family. But she didn’t have the heart to kill this helpless little human.

“Maybe. For now, the blueberries are ripe and we must get to them before the crows and the others eat them all.” So Giju’muin led the two cubs and the boy to the wild blueberry fields.

When they arrived at the fields, the bushes were blue with big juicy berries. But there were many bears already there. When those strange bears saw Mikinawk, some screeched “Human! Run!” And they scurried away. Some adults growled mightily and charged at the boy. Giju’muin put herself in front of the boy and warned them away, saying that she had adopted this human cub and that he would not harm them.

And so Mikinawk was adopted by the bears, who gave him a new name — Muinej, the Bear’s Cub.

The cubs were happy with their new brother and Giju’muin taught all three of the young ones the ways of the forest and meadowlands and waterways. Muinej rejoiced in his newfound life, almost forgetting his old life in the village. He loved the stories his mother bear told them. Indeed, he even learned to walk on all four paws at times. He almost came to believe he was a bear.

The next year, he and his brother Nidap thought up a sly plan to get more berries for themselves when they arrived again at the fresh blueberry grounds. When they saw all the bears happily feeding on the sweet berries, Nidap ran among the bushes with Muinej chasing him. Nidap began screaming “The humans are attacking. Run!” And many of the bears saw them and ran so fast they almost flew like the crows.

They stopped laughing when they saw the anger on Giju’muin’s face.

She growled a warning at them to never do that again. But there was a hint of a smile from her when she shuffled away.

The brothers, sometimes with their sister’s help, were always up for tricks on other animals. But never around their mother. And so time passed happily.

One springtime, she was teaching them how to catch smelt fish in the slower shallows of the river. Sister Ebit had hurt her leg a few days earlier when she had fallen out of a leafing birch tree, although it was healing. So she sat on the river bank. They were eating fresh smelts when Giju’muin lifted her nose to the air. “Humans!” she cried. “Follow me, my children. We must run!”

The boy thought at first that she was playing her own trick on them in punishment for what he and his brother had once done at the blueberry fields. She had a long memory.

But no. This was no trick.

They ran for the cave. But sister bear still limped and slowed them down. The mother bear knew what she must do. “There! We will hide under that big cedar tree. Now!”

So they crawled under the low hanging cedar boughs and hid in the sweet-scented shadows.

Footsteps came closer. She knew the hunters had seen them. And followed their tracks in the grass and bushes.

Sadly Giju’muin said, “I am going out to face them. When I am occupying them, Nidap, you must run to the rocky hills and do not slow down. You are big enough now to make your own way in life. Then you, Muinej, must go out and face them. Plead for your sister’s life. You are human, perhaps they will listen to you.”

And so Giju’muin scrambled out and ran away as fast as she could. The boy heard men’s excited voices. And the twang of hunting bows. The cheers of success. Spoken words he had not heard for what seemed a long time. But recognized.

“Yes, brother,” he said to Nidap. “Run that way. I will speak for our sister. We will all meet again.”

When Nidap ran out, the boy heard the men’s voices again, so he crawled out from under the cedar branches.

“See me!” he shouted to the hunters. Ten men or so stared at the naked boy in surprise.

Beyond them, he saw the body of the mother bear, arrows in her like quills from a giant porcupine. His eyes grew wet, but he had Ebit’s life to save.

“I am Muinej, once called Mikinawk! With me is Ebit, my adopted sister. Spare her!”

“It IS Mikinawk,” said one hunter. The shocked men lowered their bows.

Silently, Muinej and Ebit went over to the body of Giju’muin and shed their tears.

Around a campfire that night, the boy who was known as Mikinawk told his story, as I have just told you.

When they returned to their Mi’kmaq village, there was more weeping as his mother joyfully received him — and his new sister. His mother helped raise Ebit until the young she-bear was ready to return to the forest.

Muinej kept his bear-name. He became a great hunter. And with a heart as big as a bear’s, he always provided for his mother and others of the village in need. But he never killed a bear. And saw that his own people never hunted a she-bear when she had cubs.

He often met up with his brother Nidap and they would laugh and exchange stories of great deeds and greater meals. And when Ebit grew into an adult and had her own cubs, he would visit her and her new family at the base of a hollow tree where they denned and they would relive old times and celebrate the new.

And once a year they would join all the other bears in the wild blueberry fields.

THE END

UPDATE: I want to thank readers who gave such positive feedback to my bear story.

A common reaction was like that of Tylor Hugley: “Loved the story except mother bear’s death…” @TylorHugley.

I considered reworking that plot element. After all, I had created my own original cast of characters. And fleshed out this story of a boy who lived with bears. “Let the Mama Bear live!” I told myself. It was a sad moment when I realized that I had to follow the logic of the story as I had envisioned it.

In the versions of the Mama Bear story I’d read, the boy is unwanted and homeless. And that didn’t seem true to the Mi’kmaq way. Mikinawk would have had a loving family member, a grandmother, perhaps… I gave Mikinawk a loving mother. And reversed the European cruel stepmother story arc, giving him a cruel stepfather (somebody like Dicken’s Mr Murdstone).

Before returning to Canada as a lad, my Manx Grandmother, who loved to tell me old folktales, spoke of Bears (as well as Blackbirds, Brownies and Bugganes).

She used to tell the story of a girl who married a Viking chief who was a bear. I think now it was a Manx version of the much longer Irish story, “The Brown Bear of Norway.”

It’s a deep cultural mythos that’s always haunted me.

I wrote this Bear Story to honour our local Mi’kmaq culture.[1] And to celebrate our mystic Atlantic Canadian forests — where I have wandered most of my life.

The Bear story “Muinej The Bear’s Cub” and accompanying material on this page are copyright © by Brian Alan Burhoe. You are free to reprint “Muinej The Bear’s Cub” but please credit this author.

Did you enjoy my Bear Story?

IF SO, YOU MIGHT WANT TO READ WOLFBLOOD — MY MOST POPULAR ANIMAL YARN: “I LOVE THE HAPPY ENDING!”

IF SO, YOU MIGHT WANT TO READ WOLFBLOOD — MY MOST POPULAR ANIMAL YARN: “I LOVE THE HAPPY ENDING!”

“I JUST READ WOLFBLOOD AGAIN FOR GOOD MEASURE. ONE FOR ANY WOLF LOVER. ENJOYED IT BUT WISH IT WAS A FULL LENGTH NOVEL.” – Gina Chronowicz @ginachron

“GREAT SHORT STORY! DOES REMIND ME OF CALL OF THE WILD, WHITE FANG…” – Evelyn @evelyn_m_k

An “entertaining and affectionate” narrative in the Jack London Tradition of a lone Gray Wolf and his quest for a place in the far-flung forests of the feral North. FREE TO READ ==> WOLFBLOOD: A Wild Wolf, A Half-Wild Husky & A Wily Old Trapper

“Live Free, Mon Ami!” – Brian Alan Burhoe

Notes on this Bear Story:

[1] I first read some of those great First Nations stories in old library books many years ago. Including Mi’kmaq. And copied down the tales I most loved in Camp Fire note books.

[1] I first read some of those great First Nations stories in old library books many years ago. Including Mi’kmaq. And copied down the tales I most loved in Camp Fire note books.

The story of an unwanted boy who was adopted by bears — titled “A Child Nourished by a Bear” — appeared in LEGENDS OF THE MICMACS, collected by Silas T Rand: “A long time before either the French or the English people were heard of, there was in a certain village a little boy who was an orphan. He was in the charge of no one in particular, and sometimes stayed in one wigwam and sometimes in another, having no home of his own…”

Emelyn Newcomb Partridge also published a version of this same bear story — which she titled “Mooin the Bear’s Child” — in her GLOOSCAP THE GREAT CHIEF AND OTHER STORIES: “One day a hunter was looking for bear tracks. He found the tracks of an old bear and two cubs. And with these tracks, he saw marks like those made by the naked feet of a little child.”

October is Mi’kmaq History Month.

REMEMBER: Unceded Mi’kma’ki. Peace and Friendship Treaty 1725!

DO YOU WANT TO READ MY ANIMAL STORIES ON YOUR MOBILE CELLPHONE OR TABLET? Go to my Mobile-Friendly BrianAlanBurhoe.com…

BOY WHO WAS RAISED BY BEARS: Native American Bear Story & Legend – Muinej The Bear’s Cub – A Mi’kmaq Bear Story Retold – A free online short animal story.

American Indian, a bear story, animal stories for adults, bear stories, brown bear story, children animal stories, Civilized Bears. Camp Fire notebooks. Indigenous, kids animal stories, little bear story, Mi’kmaq History Month, Micmac. Native American Indian, native American legend, native Americans, short animal stories. Furry fiction, bear furry, bear xenofiction, xenofiction. Short bear story.