Realistic Animal Story.

NOTE FROM BRIAN: Most of the fiction on this site is written by me. There’s only one major exception. And this Animal Story is it.

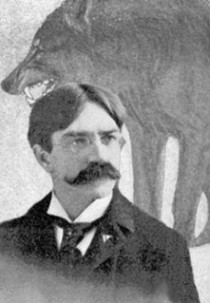

As I’ve said elsewhere, Canadian author Sir Charles G D Roberts was my first literary hero. I discovered his yarns of wild animals first in my elementary school readers. And then in well-worn hardcover books in the library.

Sir Charles G D Roberts

I was captivated from the beginning by the fact that he was writing about the very same New Brunswick evergreen forests that I loved to prowl. And then by his haunting portraits of the beings who lived there. The experienced backwoodsmen, the domestic animals, but most of all the Wild Creatures.

I was surprised at the time that, while many of Robert’s stories dealt so realistically with sudden violent death, these adult stories were available to us kids. Later, I learned that “Animal Stories” are just considered KidLit. Even when written for adults in the times of Roberts, Jack London and James Oliver Curwood. Don’t worry, this story has a happy ending…

I also didn’t know then that, while he had been abandoned by the Toronto CanLit crowd and mostly forgotten by all except some of his fellow New Brunswickers, Sir Charles had once been a beloved international best selling author. Matching writers like Rudyard Kipling and Mark Twain in sales and popularity.

Like most of his animal short stories, this one appeared first in an American magazine. And then was collected in book form. In this case, HOOF AND CLAW, which was published in 1914 by MacMillan Company, New York, London and Toronto.

THE BEAR THAT THOUGHT HE WAS A DOG: An Animal Story by Sir Charles G D Roberts

The gaunt, black mother lifted her head from nuzzling happily at the velvet fur of her little one. The cub was but twenty-four hours old, and engrossed every emotion of her savage heart. But her ear had caught the sound of heavy footsteps coming up the mountain.

They were confident, fearless footsteps, taking no care whatever to disguise themselves. So she knew at once that they were the steps of the only creature that presumed to go so noisily through the great silences. Her heart pounded with anxious suspicion. She gave the cub a reassuring lick, deftly set it aside with her great paws, and thrust her head forth cautiously from the door of the den.

She saw a man — a woodsman in brownish-grey homespuns and heavy leg-boots, and with a gun over his shoulder — slouching up along the faintly marked trail which led close past her doorway.

Her own great tracks on the trail had been obliterated that morning by a soft and thawing fall of belated spring snow. “The robin snow,” as it is called in New Brunswick. And the man, absorbed in picking his way by this unfamiliar route over the mountain, had no suspicion that he was in danger of trespassing.

But the bear, with that tiny black form at the bottom of the den filling her whole horizon, could not conceive that the man’s approach had any other purpose than to rob her of her treasure. She ran back to the little one, nosed it gently into a corner, and anxiously pawed some dry leaves half over it.

Then, her eyes aflame with rage and fear, she betook herself once more to the entrance. And crouched there motionless to await the coming of the enemy.

The man swung up the hill noisily, grunting now and again as his foothold slipped on the slushy, moss-covered stones. He fetched a huge breath of satisfaction as he gained a little strip of level ledge, perhaps a dozen feet in length, with a scrubby spruce bush growing at the other end of it.

Behind the bush he made out what looked as if it might be the entrance to a little cave. Interested at once, he strode forward to examine it. At the first stride a towering black form, jaws agape and claws outstretched, crashed past the fir bush and hurled itself upon him.

A man brought up in the backwoods learns to think quickly, or, rather, to think and act in the same instant. Even as the great beast sprang, the man’s gun leaped to its place and he fired.

His charge was nothing more than heavy duck-shot, intended for some low-flying flock of migrant geese or brant. But at this close range, some seven or eight feet only, it tore through its target like a heavy mushroom bullet. And with a stopping force that halted the animal’s charge in mid-air like the blow of a steam hammer.

She fell in her tracks, a heap of huddled fur and grinning teeth.

“Gee,” remarked the man, “that was a close call!”

He ejected the empty shell and slipped in a fresh cartridge. Then he examined critically the warm heap of fur and teeth. Perceiving that his victim was a mother, and also that her fur was rusty and ragged after, the winter’s sleep. Sentiment and the sound utilitarianism of the backwoods stirred within him in a fine blend.

“Poor old beggar!” he muttered. “She must hev’ a baby in yonder hole. That accounts fer her kind of hasty ways. ‘Most a pity I had to shoot her jest now, when she’s out o’ season an’ her pelt not worth the job of strippin’ it!”

Entering the half darkness of the cave, he quickly discovered the cub in its ineffectual hiding-place. Young as it was, when he picked it up, it whimpered with terror and struck out with its baby paws, recognizing the smell of an enemy.

The man grinned indulgently at this display of spirit. “Gee, but ye’re chock-full o’ ginger!” he said.

And then, being of an understanding heart and an experimental turn of mind, he laid the cub down and returned to the body of the mother. With his knife he cut off several big handfuls of the shaggy fur and stuffed it into his pockets. Then he rubbed his hands, his sleeves, and the breast of his coat on the warm body.

“There, now,” he said, returning to the cave and once more picking up the little one, “I’ve made ye an orphant, to be sure, but I’m goin’ to soothe yer feelin’s all I kin. Ye must make believe as how I’m yer mammy till I kin find ye a better one.”

Pillowed in the crook of his captor’s arm, and with his nose snuggled into a bunch of his mother’s fur, the cub ceased to wonder at a problem too hard for him, and dozed off into an uneasy sleep.

And the man, pleased with his new plaything, went gently that he might not disturb the slumber.

Now, it chanced that at Jabe Smith’s farm, on the other side of the mountain, there had just been a humble tragedy.

Jabe Smith’s dog, a long-haired brown retriever, had been bereaved of her new-born puppies. Six of them she had borne, but five had been straightway taken from her and drowned. For Jabe, though compassionate of heart, had wisely decided that compassion would be too costly at the price of having his little clearing quite overrun with dogs.

For two days, in her box in a corner of the dusky stable, the brown mother had wistfully poured out her tenderness upon the one remaining puppy. And then, when she had run into the house for a moment to snatch a bite of breakfast, one of Smith’s big red oxen had strolled into the stable and blundered a great splay hoof into the box.

That had happened in the morning. And all day the brown mother had moped, whimpering and whining, about the stable. Casting long distraught glances at the box in the corner, which she was unwilling either to approach or to quite forsake.

When her master returned, and came and looked in hesitatingly at the stable door, the brown mother saw the small furry shape in the crook of his arm. Her heart yearned to it at once. She fawned upon the man coaxingly, lifted herself with her forepaws upon his coat, and reached up till she could lick the sleeping cub.

Somewhat puzzled, Jabe Smith went and looked into the box.

Then he understood. “If you want the cub, Jinny, he’s your’n all right. An’ it saves me a heap o’ bother.”

II

Driven by his hunger, and reassured by the smell of the handful of fur which the woodsman left with him, the cub promptly accepted his adoption.

She seemed very small, this new mother. And she had a disquieting odor. But the supreme thing, in the cub’s eyes, was the fact she had something that assuaged his appetite. The flavor, to be sure, was something new, and novelty is a poor recommendation to babes of whatever kindred. But all the cub really asked of milk was that it should be warm and abundant.

And soon, being assiduously licked and fondled, and nursed till his little belly was round as a melon. He forgot the cave on the mountainside and accepted Jabe Smith’s barn as a quite normal abode for small bears. Jinny was natively a good mother.

Had her own pups been left to her, she would have lavished every care and tenderness upon them during the allotted span of weeks. And then, with inexorable decision, she would have weaned and put them away for their souls’ good.

But somewhere in her sturdy doggish make-up there was a touch of temperament, of something almost approaching imagination, to which this strange foster-child of hers appealed as no ordinary puppy could ever have done.

She loved the cub with a certain extravagance, and gave herself up to it utterly. Even her beloved master fell into a secondary place. And his household, of which she had hitherto held herself the guardian, now seemed to her to exist merely for the benefit of this black prodigy which she imagined herself to have produced.

The little one’s astounding growth — for the cubs of the bear are born very small, and so must lose no time in making up arrears of stature — was an affair for which she took all credit to herself. And she never thought of weaning him till he himself decided the matter by preferring the solid dainties of the kitchen.

When she could no longer nurse him, however, she remained his devoted comrade, playmate, satellite. The cub, who was a roguish but amiable soul, repaid her devotion by imitating her in all ways possible.

The bear being by nature a very silent animal, her noisy barking seemed always to stir his curiosity and admiration. But his attempts to imitate it resulted in nothing more than an occasional grunting “WOOF!” This throaty syllable, his only utterance besides the whimper which signaled the frequent demands of his appetite, came to be accepted as his name. He speedily learned to respond to it.

Jabe Smith, as has been already pointed out, was a man of sympathetic discernment. In the course of no long time his discernment told him that Woof was growing up under the delusion that he was a dog.

It was perhaps a convenience, in some ways, that he should not know he was a bear. He might be the more secure from troublesome ancestral suggestions. But as he appeared to claim all the privileges of his foster-mother, Jabe Smith’s foreseeing eye considered the time, not far distant, when the sturdy and demonstrative little animal would grow to a giant of six or seven hundred pounds in weight. And still, no doubt, continue to think he was a dog.

Jabe Smith began to discourage the demonstrativeness of Jinny, trusting her example would have the desired effect upon the cub. In particular, he set himself to remove from her mind any lingering notion that she would do for a lap-dog. He did not want any such notion as that to get itself established in Woof’s young brain. Also, he broke poor Jinny at once of her affectionate habit of springing up and planting her forepaws upon his breast.

That seemed to him a demonstration of ardor which, if practiced by a seven-hundred-pound bear, might be a little overwhelming. Jabe Smith had no children to complicate the situation. His family consisted merely of Mrs. Smith, a small but varying number of cats and kittens, Jinny, and Woof.

Upon Mrs. Smith and the cats Woof’s delusion came to have such effect that they, too, regarded him as a dog. The cats scratched him when he was little, and with equal confidence they scratched him when he was big.

Mrs. Smith, as long as she was in a good humor, allowed him the freedom of the house, coddled him with kitchen tit-bits, and laughed when his affectionate but awkward bulk got in the way of her outbursts of mopping or her paroxysms of sweeping.

But when storm was in the air, she regarded him no more than a black poodle. At the heels of the more nimble Jinny, he would be chased in ignominy from the kitchen door, with Mrs. Jabe’s angry broom thwacking at the spot where Nature had forgotten to give him a tail.

At such time Jabe Smith was usually to be seen smoking contemplatively on the woodpile. Regarding the abashed fugitives with sympathy.

This matter of a tail was one of the obstacles which Woof had to encounter in playing the part of a dog. He was indefatigable in his efforts to wag his tail. Finding no tail to wag, he did the best he could with his whole massive hindquarters, to the discomfiture of all that got in the way.

Yet, for all his clumsiness, his good-will was so unchanging that none of the farmyard kindreds had any dread of him. Saving only the pig in his sty.

The pig, being an incurable sceptic by nature, and, moreover, possessed of a keen and discriminating nose, persisted in believing him to be a bear and a lover of pork, and would squeal nervously at the sight of him.

The rest of the farmyard folk accepted him at his own illusion, and appeared to regard him as a gigantic species of dog. And so, with nothing to mar his content but the occasional paroxysms of Mrs. Jabe’s broom, Woof led the sheltered life and was glad to be a dog.

III

It was not until the autumn of his third year that Woof began to experience any discontent. Then, without knowing why, it seemed to him that there was something lacking in Jabe Smith’s farmyard. Even in Jabe Smith himself and in Jinny, his foster-mother.

The smell of the deep woods beyond the pasture fields drew him strangely. He grew restless. Something called to him. Something stirred in his blood and would not let him be still. And one morning, when Jabe Smith came out in the first pink and amber of daybreak to fodder the horses, he found that Woof had disappeared.

He was sorry, but he was not surprised. He tried to explain to the dejected Jinny that they would probably have the truant back again before long. But he was no adept in the language of dogs, and Jinny, failing for once to understand, remained disconsolate. Once clear of the outermost stump pastures and burnt lands, Woof pushed on feverishly.

The urge that drove him forward directed him toward the half-barren, rounded shoulders of old Sugar Loaf. There the blue-berries at this season were ripe and bursting with juice. Here in the gold-green, windy open, belly-deep in the low, blue-jeweled bushes, Woof feasted greedily. But he felt it was not berries that he had come for.

When, however, he came upon a glossy young she-bear, her fine black muzzle bedaubed with berry juice, his eyes were opened to the object of his quest.

Perhaps he thought she, too, was a dog. But, if so, she was in his eyes a dog of incomparable charm, more dear to him, though a new acquaintance, than even little brown Jinny, his kind mother, had ever been.

The stranger, though at first somewhat puzzled by Woof’s violent efforts to wag a non-existent tail, apparently found her big wooer sympathetic.

For the next few weeks, all through the golden, dreamy autumn of the New Brunswick woods, the two roamed together. And for the time Woof forgot the farm, his master, Jinny, and even Mrs. Jabe’s impetuous broom.

But about the time of the first sharp frosts, when the ground was crisp with the new-fallen leaves, Woof and his mate began to lose interest in each other.

She amiably forgot him and wandered off by herself, intent on nothing so much as satisfying her appetite, which had increased amazingly. It was necessary that she should load her ribs with fat to last her through her long winter’s sleep in some cave or hollow tree.

And as for Woof, once more he thought of Jabe Smith and Jinny, and the kind, familiar farmyard, and the delectable scraps from the kitchen, and the comforting smell of fried pancakes.

What was the chill and lonely wilderness to him, a dog? He turned from grubbing up an ant stump and headed straight back for home. When he got there, he found but a chimney standing naked and blackened over a tangle of charred ruins.

A forest fire, some ten days back, had swept past that way, cutting a mile-wide swath through the woods and clean wiping out Jabe Smith’s little homestead. It being too late in the year to begin rebuilding, the woodsman had betaken himself to the Settlements for the winter, trusting to begin, in the spring, the slow repair of his fortunes.

Woof could not understand it…

Woof could not understand it at all. For a day he wandered disconsolately over and about the ruins, whining and sniffing, and filled with a sense of injury at being thus deserted.

How glad he would have been to hear even the squeal of his enemy, the pig, or to feel the impetuous broom of Mrs. Jabe harassing his haunches!

But even such poor consolation seemed to have passed beyond his ken. On the second day, being very hungry, he gave up all hope of bacon scraps, and set off to the woods to forage once more for himself.

As long as the actual winter held off, there was no great difficulty in this foraging. There were roots to be grubbed up, grubs, worms, and beetles, already sluggish with the cold, to be found under stones and logs, and ant-hills to be ravished.

There were also the nests of bees and wasps, pungent but savory. He was an expert in hunting the shy wood-mice, lying patiently in wait for them beside their holes and obliterating them, as they came out, with a lightning stroke of his great paw.

But then the hard frosts came. Sealing up the moist turf under a crust of steel. And the snows, burying the mouse-holes under three or four feet of white fluff, then he was hard put to it for a living.

Every day or two, in his distress, he would revisit the clearing and wander sorrowfully among the snow-clad ruins. Hoping against hope that his vanished friends would presently return. It was in one of the earliest of these melancholy visits that Woof first encountered a male of his own species, and showed how far he was from any consciousness of kinship.

A yearling heifer of Jabe Smith’s, which had escaped from the fire and fled far into the wilderness, chanced to find her way back. For several weeks she had managed to keep alive on such dead grass as she could paw down to through the snow. And on such twigs of birch and poplar as she could manage to chew.

Now, a mere ragged bag of bones, she stood in the snow behind the ruins, her eyes wild with hunger and despair. Her piteous mooings caught the ear of a hungry old he-bear which was hunting in the woods near by. He came at once, hopefully. One stroke of his armed paw on the unhappy heifer’s neck put a period to her pains, and the savage old prowler fell to his meal.

But, as it chanced, Woof also had heard, from a little further off, that lowing of the disconsolate heifer. To him it had come as a voice from the good old days of friendliness and plenty and impetuous brooms. He had hastened toward the sound with new hope in his heart. He came just in time to see, from the edge of the clearing, the victim stricken down.

One lesson Woof had well learned from his foster-mother, and that was the obligation resting upon every honest dog to protect his master’s property.

The unfortunate heifer was undoubtedly the property of Jabe Smith. In fact, Woof knew her as a young beast who had often shaken her budding horns at him. Filled with righteous wrath, he rushed forward and hurled himself upon the slayer. The latter was one of those morose old males, who, having forgotten or outgrown the comfortable custom of hibernation, are doomed to range the wilderness all winter.

His temper, therefore, was raw enough in any case. At this flagrant interference with his own lawful kill, it flared to fury. His assailant was bigger than he, better nourished, and far stronger. But for some minutes he put up a fight which, for swift ferocity, almost daunted the hitherto unawakened spirit of Woof.

A glancing blow of the stranger’s, however, on the side of Woof’s snout — only the remnant of a spent stroke, but enough to produce an effect on that most sensitive center of a bear’s dignity. There was a sudden change in the conditions of the duel. Woof, for the first time in his life, saw red. It was a veritable berserk rage, this virgin outburst of his.

His adversary simply went down like a rag baby before it, and was mauled to abject submission, in the smother of the snow, inside of half a minute. Feigning death, which, indeed, was no great feigning for him at that moment, he succeeded in deceiving the unsophisticated Woof, who drew back upon his haunches to consider his triumph.

In that second the vanquished one writhed nimbly to his feet and slipped off apologetically through the snow. And Woof, placated by his victory, made no attempt to follow.

The ignominies of Mrs. Jabe’s broom were wiped out. When Woof’s elation had somewhat subsided, he laid himself down beside the carcass of the dead heifer. As the wind blew on that day, this corner of the ruins was a nook of shelter.

Moreover, the body of the red heifer, dead and dilapidated though it was, formed in his mind a link with the happy past. It was Jabe Smith’s property, and he got a certain comfort from lying beside it and guarding it for his master. As the day wore on, and his appetite grew more and more insistent, in an absent-minded way he began to gnaw at the good red meat beside him.

At first, to be sure, this gave him a guilty conscience. From time to time he would glance up nervously, as if apprehending the broom. But soon immunity brought confidence, his conscience ceased to trouble him, and the comfort derived from the nearness of the red heifer was increased exceedingly.

As long as the heifer lasted, Woof stuck faithfully to his post as guardian, and longer, indeed. For nearly two days after the remains had quite disappeared — save for horns and hoofs and such bones as his jaws could not crush — he lingered.

Then at last, urged by a ruthless hunger, and sorrowfully convinced that there was nothing more he could do for Jabe or Jabe for him, he set off again on his wanderings.

About three weeks later, forlorn of heart and exigent of belly, Woof found himself in a part of the forest where he had never been before. But some one else had been there. Before him was a broad trail, just such as Jabe Smith and his wood sled used to make. Here were the prints of horses’ hooves. Woof’s heart bounded hopefully.

He hurried along down the trail. Then a faint, delectable savor, drawn across the sharp, still air, met his nostrils. Pork and beans — oh, assuredly! He paused for a second to sniff the fragrance again, and then lurched onwards at a rolling gallop. He rounded a turn of the trail, and there before him stood a logging camp.

To Woof a human habitation stood for friendliness and food and shelter. He approached, therefore, without hesitation. There was no sign of life about the place, except for the smoke rising liberally from the stove-pipe chimney. The door was shut, but Woof knew that doors frequently opened if one scratched at them and whined persuasively. He tried it, then stopped to listen for an answer.

The answer came — a heavy, comfortable snore from within the cabin. It was mid-morning, and the camp cook, having got his work done up, was sleeping in his bunk while the dinner was boiling. Woof scratched and whined again. Then, growing impatient, he reared himself on his haunches in order to scratch with both paws at once.

His luck favored him, for he happened to scratch on the latch. It lifted, the door swung open suddenly, and he half fell across the threshold. He had not intended so abrupt an entrance, and he paused, peering with diffidence and hope into the homely gloom.

The snoring had stopped suddenly. At the rear of the cabin Woof made out a large, round, startled face, fringed with scanty red whiskers and a mop of red hair, staring at him from over the edge of an upper bunk.

Woof had hoped to find Jabe Smith there. But this was a stranger, so he suppressed his impulse to rush in and wallow delightedly before the bunk.

Instead of that, he came only half-way over the threshold, and stood there making those violent contortions which he believed to be wagging his tail. To a cool observer of even the most limited intelligence it would have been clear that these contortions were intended to be conciliatory.

But the cook of Conroy’s Camp was taken by surprise. He was not a cool observer–in fact, he was frightened. A gun was leaning against the wall below the bunk.

A large, hairy hand stole forth, reached down and clutched the gun. Woof wagged his haunches more coaxingly than ever, and took another hopeful step forward.

Up went the gun.

There was a blue-white spurt, and the report clashed deafeningly within the narrow quarters. The cook was a poor shot at any time, and at this moment he was at a special disadvantage.

The bullet went close over the top of Woof’s head and sang waspishly across the clearing. Woof turned and looked over his shoulder to see what the man had fired at. If anything was hit, he wanted to go and get it and fetch it for the man, as Jabe and Jinny had taught him to do.

But he could see no result of the shot. He whined deprecatingly and ventured all the way into the cabin. The cook felt desperately for another cartridge. There was none to be found. He remembered that they were all in the chest by the door.

He crouched back in the bunk, making himself as small as possible, and hoping that a certain hunk of bacon on the bench by the stove might divert the terrible stranger’s attention and give him a chance to make a bolt for the door. But Woof had not forgotten either the good example of Jinny or the discipline of Mrs. Jabe’s broom.

Far be it from him to help himself without leave. But he was very hungry. Something must be done to win the favor of the strangely unresponsive round-faced man in the bunk. Looking about him anxiously, he espied a pair of greasy cowhide “larrigans” lying on the floor near the door. Picking one up in his mouth, after the manner of his retriever foster-mother, he carried it over and laid it down, as a humble offering, beside the bunk.

Now, the cook, though he had been undeniably frightened, was by no means a fool. This touching gift of one of his own larrigans opened his eyes and his heart. Such a bear, he was assured, could harbor no evil intentions. He sat up in his bunk.

“Hullo!” he said. “What ye doin’ here, sonny? What d’ye want o’ me, anyhow?”

The huge black beast wagged his hindquarters frantically and wallowed on the floor in his fawning delight at the sound of a human voice.

“Seems to think he’s a kind of a dawg,” muttered the cook thoughtfully. And then the light of certain remembered rumors broke upon his memory.

“I’ll be jiggered,” he said, “ef ’tain’t that there tame b’ar Jabe Smith, over to East Fork, used to have afore he was burnt out!”

Climbing confidently from the bunk, he proceeded to pour a generous portion of molasses over the contents of the scrap pail, because he knew that bears had a sweet tooth. When the choppers and drivers came trooping in for dinner, they were somewhat taken aback to find a huge bear sleeping beside the stove.

As the dangerous-looking slumberer seemed to be in the way–none of the men caring to sit too close to him. To their amazement the cook smacked the mighty hindquarters with the flat of his hand, and bundled him unceremoniously into a corner.

“‘Pears to think he’s some kind of a dawg,” explained the cook, “so I let him come along in for company. He’ll fetch yer larrigans an’ socks an’ things fer ye. An’ it makes the camp a sight homier, havin’ somethin’ like a cat or a dawg about.”

“Right you are!” agreed the boss. “But what was that noise we heard, along about an hour back? Did you shoot anything?”

“Oh, that was jest a little misunderstandin’, before him an’ me got acquainted,” the cook explained with a trace of embarrassment. “We made it up all right.”

THE END

THE ANIMAL STORY

END NOTE: Many of my beloved books (and some I’ve finally been able to get!) by New Brunswick’s own Sir Charles G D Roberts have been digitized by Google and proofread by Project Gutenberg. And are readily available online for FREE eBook download, including Amazon Kindle Books.

I whole-heartedly recommend EARTH’S ENIGMAS (the first collection of his magazine animal yarns, published in 1896). THE WATCHERS OF THE TRAILS, THE HAUNTERS OF THE SILENCES, THE KINDRED OF THE WILD and HOOF AND CLAW as by Charles George Douglas Roberts. In fact, I recommend every animal tale Sir Charles ever wrote.

That same night when the moon was rising round and white…

The Life & Works of Charles G D Roberts

Born in the farming community of Douglas, New Brunswick, in 1860, Charles George Douglas Roberts grew up watching and studying animals, both domestic and wild, in the countryside, marshlands and Northwoods of Atlantic Canada. He later decided to write about those animals as they really lived.

At that time, fiction dealt with animals either as unfeeling and dangerous prey to be hunted and fished. Or as talking creatures in children’s stories, such as Rudyard Kipling’s Jungle Books. But Roberts didn’t want to write about animals in either way. Instead he was determined to write yarns about animals that caught their real emotions and thoughts, from their own point of view.

He drew fire from the beginning for presenting animals as fully feeling creatures with their own individual identities and lives. It suited many people to think of animals as unfeeling biological machines – easier to slaughter them that way.

Although Naturalist John Burroughs — who had attacked the authenticity of animal story writers Ernest Thompson Seton and Reverend William J Long (calling them “Nature Fakers”) — highly praised Roberts’ KINDRED OF THE WILD, calling it “the most brilliant collection of animal stories that has appeared.” [1]

For all the debate, Roberts also built an avid following who loved his pioneering realistic stories of animal ways. He said that “the exciting adventure lies in the effort to ‘get under the skins,’ so to speak, of these shy and elusive beings.”

For all the debate, Roberts also built an avid following who loved his pioneering realistic stories of animal ways. He said that “the exciting adventure lies in the effort to ‘get under the skins,’ so to speak, of these shy and elusive beings.”

In so doing, Charles G D Roberts created what has been called “the one native Canadian art form” — the Realistic Animal Story.

Of his realistic animal fiction, he wrote: “It helps us to return to Nature, without requiring that we at the same time return to barbarism. It leads us back to the old kinship of earth…”

He choose from the beginning to publish as “Charles G D Roberts.” When later asked what the “G D” stood for, he would snap “God Damn!” which stuck with him for years, first by his enemies, then by his wonder-filled followers.

Although his poems and other fiction earned him acclaim in his native land, it was those stories of wilderness and the creatures that lived and died there that brought him worldwide fame.

“The present writer,” Roberts wrote in his introduction to WATCHERS OF THE TRAIL, “having spent most of his boyhood on the fringes of the forest, with few interests save those which the forest afforded, may claim to have had the intimacies of the wilderness as it were thrust upon him. The earliest enthusiasms which he can recollect are connected with some of the furred or feathered kindred. And the first thrills strong enough to leave a lasting mark on his memory are those with which he used to follow — furtive, apprehensive, expectant, breathlessly watchful — the lure of an unknown trail.”

His short stories were published in the top magazines of the day, including Harper’s Magazine, Longman’s Magazine, Scribner’s Magazine, The Cosmopolitan, Lippincott’s Magazine, The Independent, The Toronto Globe, Harper’s Bazaar and The Illustrated Sunday Magazine.

In 1898, just two years after the publication of his EARTH’S ENIGMAS, Roberts was elected to the United States National Institute of Arts and Letters. In that same year, the publication of Ernest Thompson Seton’s WILD ANIMALS I HAVE KNOWN added to the popular demand for naturalistic animal stories. The Realistic Animal Story had found its audience.

With a savage growl, Kroof launched herself at him and he wrenched the door open and fled.

Roberts’ Wildlife Illustrators

Many of his hardcover books, as well as short stories in popular publications like Outing and The Century Magazine, were illustrated by Charles Livingston Bull. Bull was a beloved American artist who truly captured the free spirit of the remaining wild places.

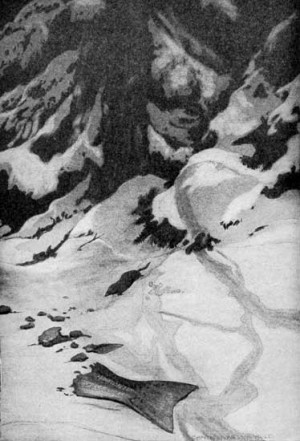

Popular Canadian artist James L Weston, known for his maritime and landscape paintings, provided illustrations for some of Roberts’ books. Fellow Canadian novelist and painter Arthur Heming, called “The Chronicler of the North,” also illustrated some of his magazine stories. American wildlife artist Paul Bransom illustrated Robert’s HOOF AND CLAW, including this story of Woof, a bear who thought he was a dog.

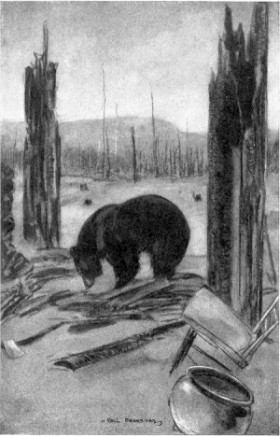

The “Woof could not understand it” drawing above is by Bransom.

The “With a savage growl, Kroof launched herself…” illustration is by James L Weston, from Roberts’ THE HEART OF THE ANCIENT WOOD, Methuen & Co, London, 1902.

And the “same night when the moon was rising round and white” illustration is by Arthur Heming, from Roberts’ “Wild Motherhood”, Outing Magazine, Feb 1901.

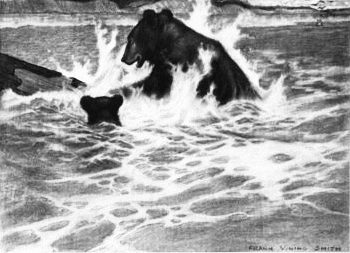

“A heart-broken bawl burst from his throat” below is by Frank Vining Smith, illustrating “From The Teeth Of The Tide” from Roberts’ THE HOUSE IN THE WATER: A Book of Animal Stories, 1908. Massachusetts-born Smith was best known for his Maritime and seascape paintings.

The other artwork on this page — The Animal Story, Rabbit Alert and Fish Dinner (below) — is by Charles Livingston Bull, illustrating stories written by Roberts. [2]

I’m not the only one inspired by Charles “God Damn” Roberts. Jack London was an avid follower. And James Oliver Curwood. And Walt Morey.

And President Teddy Roosevelt, hearing that Roberts was visiting New York, invited him to the White House to discuss his wilderness fiction. Roberts was knighted in 1935 by King George V, who called him “The Father of Canadian Literature.”

“Live Free, Mon Ami!” – Brian Alan Burhoe

==>> “A WILD WOLF, A HALF-WILD HUSKY, A WILY OLD TRAPPER!” If you want to read my free Animal Story in the Charles G D Roberts & Jack London Tradition, Click Here to Read My Popular Online Northwestern WOLFBLOOD!

[1] John Burroughs, Atlantic Monthly, March, 1903.

[2] Bull, Bransom and Heming are probably the best three wildlife illustrators of that age, sought by the top wilderness writers and their publishers.

[2] Bull, Bransom and Heming are probably the best three wildlife illustrators of that age, sought by the top wilderness writers and their publishers.

Arthur Heming made over 60 trips through the Canadian wilderness, producing some of our most beloved wildlife artwork — his iconic 1908 painting Voyageurs Shooting the Rapids is a national masterpiece.

In honour of Bull and Bransom, the National Museum of Wildlife Art in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, created the Bull-Bransom Award, given annually “to recognize excellence in the field of book illustration with a focus on nature and wildlife.” To Learn more about this Wildlife Artist award, you can visit Wildlife Art – Bull-Bransom Award.

To see more of Bull’s art, go to A Tribute to Charles Livingston Bull, Wildlife Artist…

“On hearing that Charles G D Roberts was staying in New York City for a few weeks, the normally shy artist put together a portfolio of his best work and set out to meet the popular Canadian wildlife writer.”