Algonquin Regiment & Liberation of Holland.

Out of My Father’s Shaving Box

Dad’s War, Algonquin Regiment & the Liberation of Holland

“This is yours now, Brian. He wanted you to have it.”

And my mother handed me an old wooden shaving kit Dad had made some thirty years earlier. The wood smelled of shaving cream (it still does) but now held articles of his soldiering years. It was 1967 and Dad had died from medical problems that had plagued him all the years I knew him. He was only 54, and it took me some time to realize how young that was.

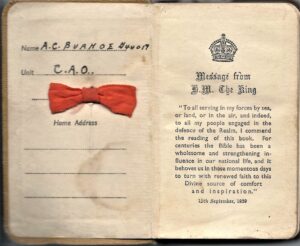

The box held his few military items. His discharge papers, showing that Pte. Albert Chester Burhoe, known to his friends as “Chester”, was demobbed from the Canadian Army (Active) in Fredericton, New Brunswick, Aug 20, 1945. Old Paybooks. Medals, including a France-Germany Campaign Star. Assorted pins such as his Army Active Service badge and his well-worn Legion pin.

The box held his few military items. His discharge papers, showing that Pte. Albert Chester Burhoe, known to his friends as “Chester”, was demobbed from the Canadian Army (Active) in Fredericton, New Brunswick, Aug 20, 1945. Old Paybooks. Medals, including a France-Germany Campaign Star. Assorted pins such as his Army Active Service badge and his well-worn Legion pin.

And three items that he had shown me years before. Each had a story.

Every Remembrance Day I take out that shaving box and replace last year’s poppy with a new one, the one I’d just been wearing.

And I look at those three items.

Algonquin Regiment History & Cap Badge

First, his REGIMENTAL BADGE. Dad belonged to the Algonquin Regiment and never hid his pride in it.

Formed on Dominion Day, 1900, the Algonquin Regiment was considered a Northern Ontario unit. Although Dad, with a number of fellow Nova Scotians, joined and trained with the regiment at the Debert Military Camp.

Formed on Dominion Day, 1900, the Algonquin Regiment was considered a Northern Ontario unit. Although Dad, with a number of fellow Nova Scotians, joined and trained with the regiment at the Debert Military Camp.

The Algonquin Regiment was a rifleman unit, including many trappers, hunters and lumberjacks from the Northwoods.

Some of them were First Nations, especially Northern Cree. Hence the motto emblazoned on the badge under the moosehead: NE-KAH-NE-TAH, in the language of the Algonquin People: “We Lead – They Follow.” First in. Often the task of the infantry, eh?

Dad fit right in. He was a good marksman. My Uncle Fulton told us the story of how, as boys (after seeing a Western), “I dared Chester to shoot a coin — a quarter — out of my fingers, as in the movie. I held it up as high as I could and Chester took his hunting rifle and — BANG! — he did it. We got a whipping for that! I was just glad that I still had all of my fingers.”

In the mid-Thirties, Dad, being the youngest son, had gone to work in the lumber camps of New Brunswick. He sent money home to help keep the family farm going. He was working as a carpenter at the Saint John shipyard when the War broke out. Although he was designated as having an essential job, he enlisted in the No 7 District Depot on June 3, 1941.

The Algonquins steamed out of Halifax’s Bedford Basin on the ocean liner Empress of Scotland on June 10, 1943.

The Empress dodged German U-boats on its long unescorted voyage to the bomb-damaged city of Liverpool, England.

For a year, they continued to train and prepare on British soil, mostly at an Army base in Ripon, Yorkshire. They trained with other Canadian units. Including the Argyll Highlanders, the Lincoln and Welland Regiment, and the South Alberta Regiment.

In that year, he took leave when he could, meeting a young double-decker bus conductress. A Yorkshire lass who took his fancy. Together, they took long walks on Ilkley Moor, saw the latest movies (Alan Ladd was a favourite of theirs) and stopped at the Hope & Anchor for a “wee drop of Scotch.” Before he left for Normandy in June ’44, they married.

Algonquin Regiment & the Liberation of Holland

The Algonquins’ battle-filled progress from Juno Beach through France, Belgium, the Netherlands and into northern Germany is well recorded. [1]

The “Long Chase” through the summer and autumn would make regimental history. Tilly-la-campagne, Falaise Road, the Seine district, the Scheldt, the Lower Maas, the Month of Dikes. The Liberation of Holland, especially Steenbergen, Waalwijk and Wierden. And, in winter, into the Rhineland…

As soon as they arrived, the Algonquins found themselves facing the 1 SS Panzer Division. Described as “quite the toughest troops the Germans had in Normandy.”

Their first mission sounded simple: liberate the French village of Tilly-la-campagne. And drive through and behind German lines to take control of the Caen-Falaise road. Word came down later that in that first operation all four Companies had lost a total of 128 men, killed or missing.

“We jumped right into the fire, eh?” was all Dad would say.

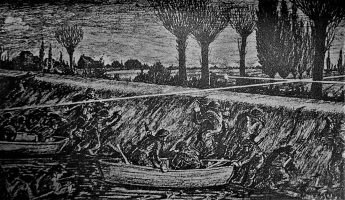

By September, the Algonquin Regiment (including Company D, Dad’s Coy) was ordered to cross the Belgium Leopold Canal and take the far-bank positions held by the Germans before enemy reinforcements arrived.

Crossing at night by canvas assault boats then pushing ahead on foot, they learned the hard way that the German reinforcements were already in place. (“The enemy sent wave after wave of men against our battered forward positions” – Major George L Cassidy.) And found themselves cut off from support and supplies.

Ammunition got so scarce that the order of the day was “One round, one German.” Our guys even searched the German prisoners they had taken for loose bullets they could use in captured enemy weapons.

The next day, the Canadian artillery lay down a heavy smoke screen. The trapped Algonquins were able to get back to their assault boats and return to the Canadian-held side of the canal. Their German prisoners wanted to go back with them and even helped wounded Algonquins cross the canal. Some men had to swim over.

When their casualties were tallied, they had 153 men dead or missing. Among the dead was Father Mooney, their field chaplain. [2] Just 48 hours later, they were back in the fire.

Algonquin Regiment & the Liberation of Holland II

And by the first of November, our Algonquins were fiercely battling the entrenched enemy at Welberg, on their push to liberate the vital agricultural town of Steenbergen. The Germans were newly reinforced by Hermann Goering Paratroops.

On November 5th, they were welcomed by throngs of people in the streets of Steenbergen.

Dad spoke little of the battles they endured.

He told me of the better times. His friendship with First Nations soldiers, who taught him (although he was already an experienced woodsman) how to “listen” to the forest — something he tried to pass on to me. Out of those yarns, I developed an image of Native and English Canadians, not antagonists, but standing side by side, with the word CANADA on both their shoulders. Fighting our common enemies and building our uncommon nation.

And the cold night he and a Cree buddy were at the front line “along the dikes” when suddenly the night lit up above their heads. A jeep had stopped at the top of an embankment behind them. The jeep’s bright lights began to draw German fire. A lot of it. Bullets spattering in the damp soil, and more loudly off rocks. “Got to be officers,” said Dad.

“Chester,” said the other, putting his bolt-action Lee Enfield rifle to his shoulder. “You take the left headlight — I’ll take the right.” So they did. And the night went dark again. And two young officers jumped out of the jeep and ran off. Dad heard later that the two had been fresh from an officers’ training centre in Canada. The official story told by the brass was that an unknown drunken Private had stolen the jeep.

The welcome the Canadians received when they liberated Holland has forever after brought tears to the eyes of aging soldiers who were there. The Algonquins were certainly given a warm welcome. “We were treated like family,” said Dad, who years later was still touched by the memory.

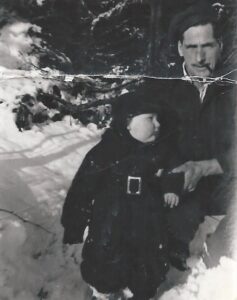

Which leads me to the second item, THE PHOTO OF A HOLLANDER GIRL.

That photo says a heck of a lot. The Hollander girl in the old snapshot is showing where the girls escaped to when the German soldiers were heard approaching. Under a hay stack, in an underground hideaway. And that says it all, doesn’t it? When the German soldiers came, the girls hid away. When the Canadian soldiers came, they showed the Canadians where they had hidden from the Germans. We were the Good Guys. Family.

After the Liberation of Holland: Christmas Eve, 1944

They spent Christmas Eve, 1944, in Sint-Michielsgestel. It was a cold, clear day where they enjoyed an early Christmas dinner, beer and carols sung by Canadian nurses. Christmas Day began the storming through Belgium and the drive into Germany.

And by frigid February, Operation Blockbuster would be underway.

The road to Germany lay through the Hochwald Forest.

The Battle for Hochwald Gap has been called one of the “Greatest Tank Battles,” and it was. As the History Channel said, in introducing the Hochwald episode in their televised series: “In February 1945, the First Canadian Army launches an attack to cross the Rhine and enter the German heartland. This is the story of the struggle for the Hochwald Gap. The final obstacle blocking the Allies, which the Germans are determined to hold at any cost.” [3]

The Germans controlled the heavily forested terrain leading into the Rhineland.

They were hidden and dug in with artillery, mortars, MG-42 machine guns and anti-tank weapons. Overlooking the open area through the forests called the Hochwald Gap. The Gap was a wide, cleared stretch through which a road and railway tracks rolled.

Supported by Canadian Sherman tanks and possible Allied air cover, it would be the job of the Algonquin Regiment, who were trained and experienced in forest warfare, to cross the exposed Gap and engage the enemy among the tall silver fir trees.

“The main Canadian effort was the infantry’s. For until the enemy had been driven out of the woods and particularly from the commanding ground south of the railway there seemed little chance of our armour breaking through to the east.” [4]

March 2, 1945. Morning. Hochwald Gap.

Due to winter storms, supporting Allied aircraft (including the critical Typhoon light bombers) were grounded. For Dad, whose D Company was tasked with capturing the bridge over the Hohe Ley Stream, it got really bad when the Canadian Sherman tanks suddenly withdrew from the field. Which left D Company totally exposed and on their own.

Their only protection was their hand-shovelled slit trenches and fox holes, hastily dug in the frosty ground within clear sight of the evergreen forest, their objective.

The mystery of why our tanks retreated was never fully explained. And not even mentioned by the men of the tank division who were quoted in the History Channel episode. Although the Official History of the Canadian Army blamed it on “deadly anti-tank fire” from the Germans in the forest.

Major George L Cassidy, a commander in the Algonquin Regiment, later wrote:

“At any rate, they (the Canadian tanks) pulled out about 7:45, and the infantry force had to cling to their slits (trenches) in desperation from that time on.

“As it became evident that there were no tanks in D Company’s position, the German armour became bolder. A German Tiger tank appeared very close in on the left flank, with infantry behind it…

“Meanwhile, on the right flank, a group of enemy tanks supported their infantry on a move to the rear of D Company’s feeble little handhold and little could be done to stop it…

“In the next few moments, the enemy had succeeded in virtually encircling D Company. Capt. Jewell was killed by a shell-burst, others were wounded, and the little garrison, leaderless, bewildered, and far from assistance, was overrun.

“The bold gamble had been lost. Not because of any lack of determination or courage of the men and their leaders, but because of a heart-breaking series of difficulties and misfortunes.” [5]

That battle was over and Mum would receive a telegram telling her that Dad (she called him “Canuck”) was “Missing in action, presumed dead.”

Dad regained consciousness with a German soldier treating his left side. He was numb there — at first. A lot of blood. He gradually figured out that, being in a lone observation fox hole ahead of the rest of the Company, he had been picked off by an enemy sniper. The bullet had torn though his left collar bone and gone out the back with bits of bone and making a bigger jagged wound.

“We hated the German snipers,” Dad told me years later. “But this one was a good shot. I didn’t give him much of a target.” For the rest of his life, Dad would have trouble getting use out of that arm.

What followed was a grueling trip under dark German skies. Marching on foot, cold open trucks, colder railway cattle cars, lots of high-pitched shouting from their captors. And a German officer, complete with monocle, asking Dad, “Why do you fight our Fuhrer?”

Stalag 11B, Fallingbostel, was in the Lüneburg Heath region of North Germany.

Not much fun. There were already some British paratroopers and men of the US Army Air Corps imprisoned there. Close by were Russian prisoners. The Soviets had no active Red Cross. And their captive soldiers, abandoned by Moscow, were dying by the hundreds from brutal treatment, disease and starvation. [6]

Dad, weak from his wound, developed jaundice and lockjaw (tetanus), and would soon be suffering from malnutrition. The Germans basically provided turnips for food, little medication and no warm clothing.

Dad always praised the Canadian Red Cross for their packages. Which contained some canned food like corned beef and luncheon meat, dried fruit, tea, milk powder and chocolate bars. As well as knitted wool socks and mittens handmade by women back home.

And he had the third item: a NEW TESTAMENT. Dad had carried it on him since landing in Normandy. He was a Baptist and he loved to read, so he read the Biblical passages. He may even have been inspired by the introductory message from H M The King, who made sure that all soldiers fighting for Britain got a copy of this little gold book. [7]

Dad was also inspired by the little bow of orange ribbon pinned in the inside cover.

That bow was given to him by a member of the Holland Resistance movement.

The Resistance was a group of daring men and women who carried out sabotage, smuggled out downed Allied airmen, performed intelligence gathering and much more. Always aware that getting caught got you beaten and shot. And the Gestapo had its own turncoat locals out there looking for them. The only form of identification among these freedom fighters was this little orange bow, pinned secretly in their clothing. “I give you this in gratitude,” the Resistance fighter told Dad. “It is blessed.”

Dad would open the Book and look at the orange ribbon. If the brave people of Holland could survive so stoically under the iron-heeled fascist occupation for five long years, he could hang in there…

On a rainy April day, after hearing explosions in the distance, our guys noticed that their guards had quietly disappeared into the mist. Now all they could hear was dripping rain. After long minutes of tense silence a heavy Humber Mk IV Armoured Car of the British 8th Recce (14th Canadian Hussars) smashed through the fortified front gate of Stalag 11B. “It’s one of ours!”

The prisoners were liberated.

Gaunt from malnutrition, the freed soldiers weren’t allowed to raid the German store-rooms. On orders of the British medical staff, Dad was fed a small serving of pea soup. “It was all I could hold anyway.” For the next few days meals consisted mainly of orange juice and vitamin pills.

In his letter to Mum from the prison camp, dated April 20, 1945, he began: “Edna Dear, Am going to drop you a line or two to let you know all is well with me. As you may know, I’ve had a brief spell as a prisoner and can’t say that I’ve enjoyed the experience. That’s over now tho and I hope to be seeing you very soon…

“…I do hope Edna that all has been going well with you and you’ve not been doing too much worrying. Give my very best wishes to your Dad, Mum & All. I’m looking forward to sampling some of your mother’s cooking. And if I feel able, maybe some of my wife’s too. I ducked then just to be on the safe side… Your Canuck.”

Thanks, Dad. Miss ya.

DEDICATION: This post is written in remembrance of my Father, of course.

Also in proud memory of all the other War Vets it’s been my honour to know and grow up among. And of all members of the Algonquin Regiment, especially those Dad served with and who he never forgot. God Bless you! You safeguarded our Freedom.

To see more of our family history, including Dad’s life after his liberation, go to The Life & Works of Brian Alan Burhoe

OUT OF MY FATHER’S SHAVING BOX: Dad’s War, Algonquin Regiment & Liberation of Holland

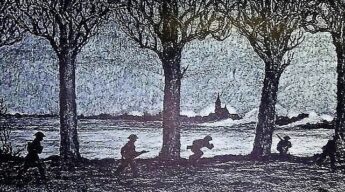

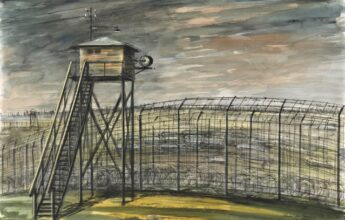

NOTE ON IMAGES: Old Photos are from our Family Albums. Pen and ink illustrations “Algonquin Night Landing Across the Leopold Canal, Sept. 13, 1944” & “Algonquin D Company Right-Hook Into Welberg, Nov 2, 1944” are by Major G L Cassidy, from his book WARPATH: The Story of the Algonquin Regiment 1939-1945.

The snapshot “Men of Algonquin Regiment, Hochwald area, March 1, 1945” was taken by Jack H Smith, Canadian Army Film and Photo Unit. And “The Wire, Stalag 11B, Fallingbostel, Germany” is an ink and wash drawing made by Australian war artist Alan Moore on-scene in 1945.

Algonquin Regiment Footnotes & Follow-ups:

[1] To read more about the Algonquins, Click Here: Canadian Army – The Algonquin Regiment – History.

[1] To read more about the Algonquins, Click Here: Canadian Army – The Algonquin Regiment – History.

For a case study of the Algonquin Regiment from their 1944 landing at Juno Beach till the end of September of that year (“weeks of endless battles and heavy casualties without any reinforcements” including “hand to hand combat in enemy-defended buildings”), Go To Rebuilding Trust: The Algonquin Regiment at War, July-September 1944.

And you can see my post about the Algonquin’s own Regimental newspaper: TEEPEE TABLOID: Voice of Algonquin Regiment in WW2 Holland & Canada. Among its letters and news stories were the “Hoiman the Goiman” cartoon that reflected D Company’s experience crossing the Leopold Canal.

[2] “Padre Thomas Mooney, from Hamilton, Ontario, was killed by shellfire while ministering to wounded a few weeks after D-Day. He was buried in the Canadian cemetery at Eccloo, Belgium. As a tribute, the Protestant chaplains of his formation served as pallbearers.” Daniel Aloysius Casey, A White Knight of God, Kingston, Ontario: The Canadian Register Press, pp. 6–35, 1945.

[3] The “Greatest Tank Battles” series was produced by National Geographic. And shown on the History Network in Canada, the Military Network in the U. S., and on Discovery Networks throughout western Europe and elsewhere.

[4] “…until the enemy had been driven out of the woods…there seemed little chance of our armour breaking through to the east.” Official History of the Canadian Army. HyperWar: The Victory Campaign, Chapter 19, The Battle of the Rhineland, Operation Blockbuster, 22 February – 10 March 1945. Canadian Army: HyperWar – Hochwald Gap – Victory – Battle of the Rhineland.

Algonquin Regiment – An Essential Book:

[5] “…a heart-breaking series of difficulties and misfortunes.”

Major Cassidy’s account of that battle was based on a report from a D Company survivor who was able to escape back to Canadian lines.

Major Cassidy’s account of that battle was based on a report from a D Company survivor who was able to escape back to Canadian lines.

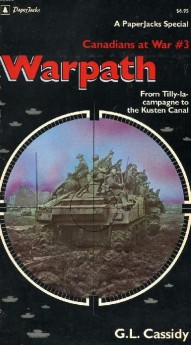

From G L Cassidy’s book, WARPATH: The Story of the Algonquin Regiment 1939-1945, published in 1948 by Ryerson Press, Toronto. And later reprinted as a quality trade paperback in 1980 as #3 in the PaperJacks Canadians At War Series, retitled WARPATH: From Tilly-la-campagne to the Kusten Canal. Illustrated with photos, war art, cartoons and detailed maps.

Major Cassidy served with the Algonquins for the entire Second World War and writes with firm knowledge of the subject, as well as understanding and moments of sentiment and humour.

With the many books being released celebrating our stories of the two world wars, this one surely should be back in print.

G L Cassidy was also the author of ARROW NORTH: The Story of Temiskaming.

[6] If a picture’s worth a thousand words, then this photo of “Newly Liberated British POWs of Stalag XIB” says a lot: Collections US HMM.

The Other Essential Book:

[7] Message from H. M. The King “To all serving in my forces by sea, or land, or in the air, and indeed, to all my people engaged in the defence of the Realm, I commend the reading of this book. For centuries the Bible has been a wholesome and strengthening influence in our national life, and it behoves us in these momentous days to turn with renewed faith to this Divine source of comfort and inspiration.” 15th September, 1939

OUT OF MY FATHER’S SHAVING BOX: Dad’s War, Algonquin Regiment & Liberation of Holland – by Brian Alan Burhoe

UPDATED November 11, 2023

4 Responses to OUT OF MY FATHER’S SHAVING BOX: Dad’s War, Algonquin Regiment & Liberation of Holland

Larry Cole says:

September 19, 2016 at 4:01 pm

I appreciated reading your post on your father. I only recently saw it. My father was also in the Alqonquins in D company. He was also in the Hochwald Gap on the morning of March 2, 1945. His first cousin, who was also in the unit, died that morning, and Dad went to Stalag IIb. (I have his wooden prison ID tag that he had to wear around his neck).

I asked Dad why the tanks pulled out and left the infantry there. His reply was that the two captains could not agree. The tank captain said he was too exposed and would lose all his tanks if he stayed there. Captain Jewell said his orders were to hold firm and not pull back. Because there was no radio contact, and no higher ranking officers around, they both did their own thing.

Brian Alan Burhoe says:

September 20, 2016 at 9:41 am

Hi Larry

Thanks for your reply. I added it to the posting, but if you don’t want it made public I can take it off.

“Dad’s War” was difficult to write but I wanted to honour Dad and the men he served with and worked with.

Like most vets, Dad told me stories growing up about the good times and the funny times he’d had with his comrades – not many about the bad. He spoke a lot about the days they spent with the local people of Holland they had helped liberate. Good times for our guys.

Dad passed just weeks before I graduated high school and I went to work with same Highways crew he’d worked with. It was from those guys I got some of the darker details of his War (as well as from Mum in later years). Guess a lot of Vets told each other things they wouldn’t tell others.

The guys mentioned that there had been an article (with diagrams showing positions) in the Legion magazine about that battle. But I’ve never found it. It must have been published in late Sixties.

At least there was Major Cassidy’s WARPATH for details. Not a good feeling the first time I read “A. C Burhoe” in the Missing section of “Casualties from 26 Feb – 3 March/45.” Just one name of many. Next to Dad’s name I see “D. M. Cole.”

One of the things I’m left with after all these years is his immense pride in serving with the Algonquins. And another is his gratitude and respect for the Canadian Red Cross – those packages the guys received in 11B kept them alive. I’ve given to the Red Cross whenever possible.

Keep well,

Brian

Brian Alan Burhoe says:

September 21, 2016 at 9:44 am

Thanks for your reply, Brian.

Dad only passed away last year, and I found that as he grew older we had some good conversations about the war. He obviously was younger than your Father, as Dad was still only 19 when they were liberated from the prisoner of war camp. He did say he was down to 90 lbs by that time.

I also had the opportunity to meet another of the men in their unit, Ivan Sloss I believe his name was, who was with the Captain and my father’s cousin when they died in the German counterattack.

Dad did not mention anything about snipers, but did say that a machine gun was sweeping the area they were in, and that they all kicked out depressions in the soft earth to keep below it’s fire. He also said that there was a tank (German) that kept peeking out from behind a barn and firing at them.

Apparently there was a bag of PIAT shells lying out in the open.

Dad said that one of the guys yelled out something to the effect of ‘a Victoria cross to who ever grabs those shells’, but his comment was that everyone knew the machine gunner also was watching them.

Dad also had a collection of things from the war that I did not know he had until it was too late. These included the tag he wore at the prisoner of war camp. He also had the telegram sent to my grandmother announcing he was missing in action, and then one after they were liberated announcing he was alive. My grandmother had already lost her oldest son in Italy (Royal Canadian Regiment) so it is hard to imagine how difficult a time it must have been for her.

He had talked about a bullet with a wooden head he took off of a German prisoner once, which I was surprised to find in there. Also a box full of new death head pins he got off somebody.

It was difficult for Dad to talk about a buddy he lost in the camp due to illness. He did chuckle when he talked about one of the guards who he said they referred to as ‘one eyed Joe’. Apparently he had lost an eye in Russia. Apparently this guard yelled a lot.

This past Summer my wife and I along with one of our sons where in Germany for a wedding. (A former exchange student). I was able to find the spot in the Hochwald gap where they were overrun. It is beautiful farmland now. No hint of the devastation of early March, 1945. The grave of my Dad’s cousin in Holland is immaculately kept by the Dutch. It is pretty sobering to see those rows of young men buried there.

Thanks, Larry

Brian Alan Burhoe says:

September 21, 2016 at 9:56 am

Hi Larry

Yes, thanks for the answer. Liked the “Victoria Cross to…” quote. Never knew that. “Wooden bullets” is a new one on me, too.

Dad had his 32nd birthday three days after they landed in France. Mum said that Dad had been offered a chance to stay in England at a desk job at the rank of Corporal but he “insisted on going with his comrades to fight Hitler.” There was some pride in her voice when she would say that – but I think she was miffed, too.

I’m only aware of there being one Algonquin comrade of his in the Saint John region. Don’t remember his name but I know that he asked Dad to help him sponsor a Russian POW who did not want to go back to the Soviet Union.

Told my brother Ray about your response. He was only ten when Dad passed and is just as interested in what happened during the War.

Gives us more to think about on D-Day remembrances and November 11th, eh?

Keywords: #VE80, Netherlands80, Algonquin Regiment liberation of Holland, Algonquin regiment ww2, Canadian war art, stalag xib fallingbostel, Canada, DDay 80, D-day 2025, VE Day 80. Teepee Tabloid, Hoiman the Goiman cartoon.