Cecil B DeMille of Hollywood…

Cecil B DeMille, Call of the North & Tikah People – aka Tiger Indians.

Written by Brian Alan Burhoe, creator of Civilized Bears.

Here’s a great story about Cecil B DeMille and the Tikah People. And the making of the classic silent movie The Call of the North.

Cecil B DeMille’s The Call of the North Reviews

“The Call of the North is the latest and beyond question the best of the Lasky photoplays produced under the direction of Cecil B DeMille and Oscar C Apfel.” – The New York Dramatic Mirror, August 19, 1914.

“Back to the days when the Hudson Bay Trading Company exercised a sovereign and undisputed sway over the great fur-bearing country of the North. The word of the Chief Factor (Company Governor) was law. Indeed, there was no other law!

“The Chief Factor plans a terrible punishment.

“He has independent trader Graeham Stewart brought before him. And despite all of Stewart’s protests, sentences him to La Longue Traverse… the Journey of Death.

“He has independent trader Graeham Stewart brought before him. And despite all of Stewart’s protests, sentences him to La Longue Traverse… the Journey of Death.

“This was a favorite punishment dealt by the Company. And the Factor vengefully inflicts it on Stewart. He who is to enter upon the fatal journey must go without food and weapons. An Indian called ‘the Shadow of Death’ is sent with him to follow close… For five days Stewart wanders through the wilderness and dies miserably in the trackless forest.

“Twenty years pass. Stewart’s son Ned is caught trading in defiance of the Factor. He is, like his father, sentenced to the Journey of Death. The Factor’s daughter Virginia, however…” Review of Call of the North by W Stephen Bush, The Moving Picture World, August 22, 1914. See Complete MPW Review below…

Cecil B DeMille, The Call of the North & the Tikah People — aka Tiger Indians…

Known best for his bankable box office blockbuster movies like The King of Kings (1927), Cleopatra (1934), North West Mounted Police (1940), Samson and Delilah (1949), The Greatest Show on Earth (1952) and The Ten Commandments (1956), Cecil B DeMille made 70 films in his career.

His fourth film, The Call of the North (1914), was his first international smash hit.

And therein lies a tale.

Here’s the great story (I’ll make it a short one) of Cecil B DeMille, the Tikah People and the creation of the silent movie The Call of the North.

The critically acclaimed film had everything going for it.

The critically acclaimed film had everything going for it.

It was based on a bestselling novel. Set in the then-popular Canadian Northcountry. Filmed in wilderness locations. Starred popular stage actor Robert Edeson in the twin roles of Graeham and Ned Stewart. And used real First Nations actors. The movie caught the public fancy. [1]

Through 1914, director/screenwriter Cecil B DeMille was quoted in a number of the informative “Talk Shop” columns in The Moving Picture World trade journal. He told about the filming of The Call of the North. DeMille said from the first that he was determined to use “actual Canadian Indians” in his new Northwoods-set movie. [2]

When the film went into rehearsals, Western writer Stewart Edward White spent four weeks in Canada. His novel CONJUROR’S HOUSE: A Romance of the Free Forest was the basis of DeMille’s screenplay. DeMille spoke of White’s “intimate knowledge of the Canadian Northwest. Where he has spent practically all of his life. He will be engaging Indians and various types significant of the Northern Woods.” [3]

Stewart Edward White, for this movie, is considered the first Technical Advisor.

At that time, an impending “Great War” between the British and Germany dominated Canadian conversation. Many Northern Cree and Algonquin men had already left their homes to enlist in the Canadian Army. But not a single Tikah had joined up. So author White was able to hire as many of them as he wanted, paying their expenses south.

The Tikah, or — as the Americans called them — Tiger Indians, were known as great canoe makers and paddlers. As well as builders of strong birchwood dog sleds.

The big beautifully decorated six-fathom North Canoes (DeMille: “a certain type of canoe now peculiar to the Tiger Tribe Indians”) had long been used in the Canadian North. By the American Fur Company and North West Company voyageurs and other, smaller independent fur traders throughout the forested Northcountry. The Hudson’s Bay Company had early-on changed from canoes to their bigger Orkney-designed York Boats.

The Tikah still made a few trade canoes into the early 20th Century.

In other “Talk Shop” columns, DeMille explained that “no stone was left unturned to make the picture absolutely true to the life portrayed.” He had brought in “eighteen big Tiger Tribe Indians with authentic canoes from Ahitiba, Canada, far north of Winnipeg.”

But when the eighteen Tikah got off the steamship at San Francisco proudly carrying two big traditional freighting canoes, they were met by Demille’s assistant Oscar Apfel. Who told them that they would be filmed paddling canoes made by the Lasky Company prop department. He also showed them sketches of the small decrepit “birch bark boats” used in the movie.

The Tikah reaction to this news was never printed.

Two of the prop canoes sank during filming.

This is the story told in the Ahitiba Northcountry for years afterward:

When the Tikah had fulfilled their acting commitment, they were offered railroad tickets to take them as far as Seattle, Washington, “on Canada’s doorstep.” Six men accepted the tickets.

The other twelve asked about their freight canoes. And were informed that only one of their big canoes could be found. Those Tikah demanded that they and their North Canoe be trucked to the Pacific Ocean. On a still morning in late June, 1914, they launched their supplies-laden canoe from a bay north of San Francisco (possibly Humboldt Bay). And bravely paddled north into the sweeping ocean. They never returned home.

Weeks later, the first group of six “actual Canadian Indians” arrived in East Selkirk, Manitoba on the brand new Canadian Northern Railway. The six quickly purchased two Ojibway canoes and launched them on the Red River. As they paddled away they were heard singing, as one townsman reported, “old voyageur songs and some wild Indian chants.” They were still singing when they reached their own Ahitiba homes on what was then called Lak Angelique.

And years later an old Tikah with a face grooved like pine bark would softly speak to those who would listen. “When I was young I went to Hollywood to be in a movie. The story it told was not true. And then it was.”

So say the Tikah People, also known as Tiger Indians.

Read more about the Tikah People! See my WOLFBLOOD: An Animal Story in the Jack London Tradition – Wild Wolf, Half-Wild Husky & Wily Old Trapper – written by Brian Alan Burhoe

“Live Free, Mon Ami!” – Brian Alan Burhoe

IMAGE CREDITS:

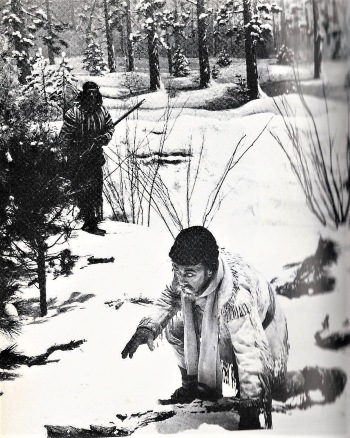

- “The Journey of Death” scene at upper left is a production still from DeMille’s The Call of the North. From my own Northern History digital album.

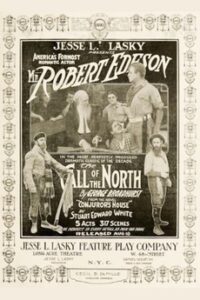

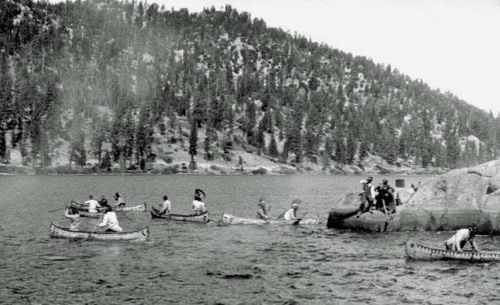

- Cast & Crew of The Call Of The North, Big Bear Lake, 1914, on-location group portrait released by Jesse L Lasky Feature Play Company.

- The Call of the North movie poster, released worldwide on August 10, 1914, by the Jesse L Lasky Feature Play Company.

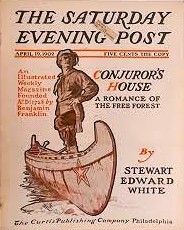

- The Saturday Evening Post, April 19, 1902 featured Stewart Edward White’s CONJUROR’S HOUSE: A Romance of The Free Forest, basis for the screenplay of The Call of the North.

- “DeMille filming the big Indian raid” of the movie is from the Rick Keppler Collection. Rick was a Big Bear Lake local photographer who restored old prints. He pointed out that the cloudy area on the “Indian raid” print “is not an imperfection with the photo, it is smoke from an actor’s gun.”

- The painting of the three six-fathom canoes is called Canoes in a Fog, Lake Superior. The piece was done by the great Canadian artist Frances Anne Hopkins (1838 – 1919).

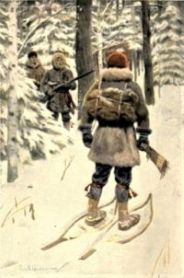

- The illustration at the bottom of this page is by Philip R. Goodwin (1881-1935), from White’s novel THE SILENT PLACES. Goodwin’s illustrations of the Northwestern wilderness and wildlife appeared in magazines, books, calendars and advertising. He’s remembered most today for his “Horse & Rider” design of the Winchester Rifles trademark.

“Twenty years pass…”

“Stewart’s son Ned is caught trading in defiance of the Factor and is, like his father, sentenced to the Journey of Death. The Factor’s daughter Virginia, however…” Review of Call of the North by W Stephen Bush, The Moving Picture World, August 22, 1914. See Complete MPW Review.

[1] This movie, and the novel it was based on, revealed a cruel form of punishment in the pre-Mounted-Police era in the Far North of Canada: La Longue Traverse, the Journey of Death.

As a shocked Bioscope reviewer would write: “There is a law in the North that, if a man commits murder, or helps one who has committed murder, the guilty party will be driven off into the snows and deprived of food, fuel or weapons until he is dead.”

The tyranny of the Fur Company Chief Factors was extreme. They were all-powerful businessmen with no training in judicial, police or military procedures (or self-discipline). Their “word was law,” even for women they wanted. La Longue Traverse, also known as The Journey of Death, was another result. Often the “guilty” man thrown into the wilderness was innocent, just someone the arrogant Factor disliked or no longer needed.

“There is a law in the North…”

As the Bioscope reviewer’s “There is a law in the North…” indicates, moviegoers were left with the idea that The Journey of Death was still being used in Canada. When The Call of the North went into remake in 1921, a riled Hudson’s Bay Company launched a lawsuit against Famous Players-Lasky. And won, the American judge ruling that “The greedy and powerful Robber Barons of the North American wild frontier do not exist in the Twentieth Century.”

As Pierre Berton concluded: “The court held that the movie distorted conditions in Canada as they existed after 1870. After that Hollywood was more careful about identifying its factors as Hudson’s Bay men.” (pg 81, HOLLYWOOD’S CANADA: The Americanization of Our National Image, McClelland and Stewart Ltd, Toronto, 1975).

For more on the history of the Fur Trade, see Hudson’s Bay Company.

In a Letter…

[2] In a letter to Samuel Goldfish (later known as Samuel Goldwyn), DeMille wrote, “I challenge anyone to find an incorrect detail in The Call of the North. The only point in this picture which I believe might be opened to criticism is that the piece of plug tobacco used in the second reel is wrapped in paper and paper was a rare article in Dog River. But Stewart Edward White, the author, sportsman, explorer informs me that it is not at all impossible that a special treasure might have reached Dog River wrapped in paper.”

Michigan-born Stewart Edward White wrote 50 books in the first half of the 20th Century, most of them set in the Canadian and American wilderness. Reader favourites include THE LAND OF FOOTPRINTS, CAMP AND TRAIL, THE BLAZED TRAIL, THE RIVERMAN, THE FOREST, THE SILENT PLACES (a personal fave) and CONJUROR’S HOUSE: A Romance of the Free Forest.

Michigan-born Stewart Edward White wrote 50 books in the first half of the 20th Century, most of them set in the Canadian and American wilderness. Reader favourites include THE LAND OF FOOTPRINTS, CAMP AND TRAIL, THE BLAZED TRAIL, THE RIVERMAN, THE FOREST, THE SILENT PLACES (a personal fave) and CONJUROR’S HOUSE: A Romance of the Free Forest.

Among his fans was Theodore Roosevelt.

The illustration to the left is by the accomplished Philip R. Goodwin, from White’s THE SILENT PLACES, McClure, Phillips & Co, New York, 1904.

I wrote this Historical Short Story to honour one of the early Hollywood scriptwriters who gave us amazing Northwestern epics. ==> Cecil B DeMille, Call of the North & Tikah People – aka Tiger Indians